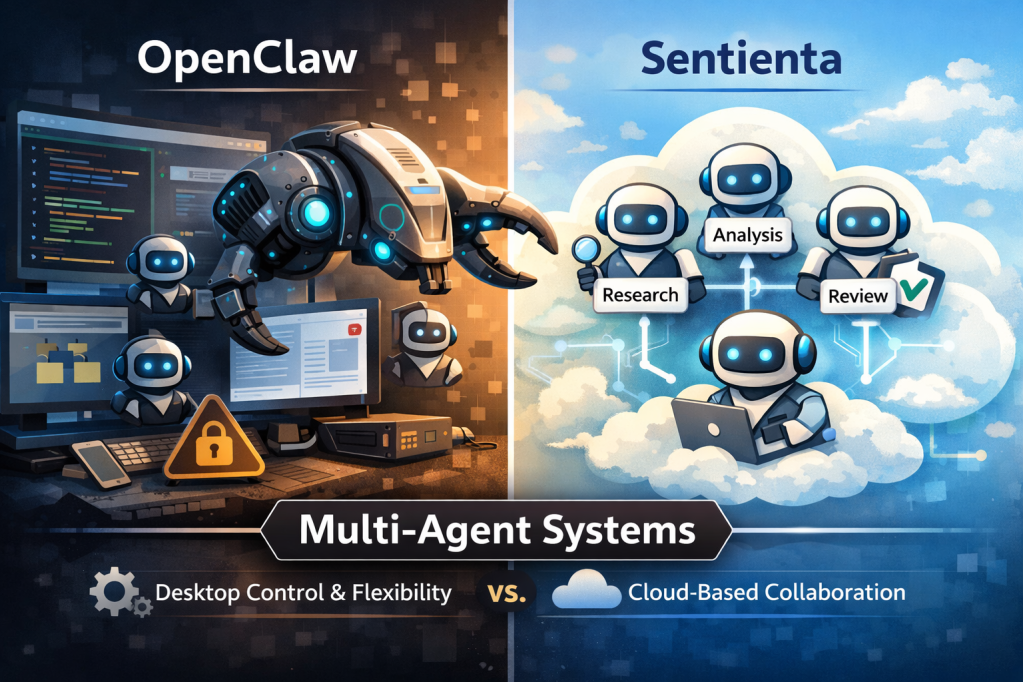

OpenClaw is having a moment—and it’s easy to see why. In the developer community, “desktop agents” have become the newest proving ground for what AI can do when it’s allowed to take real actions: browsing, editing, running commands, coordinating tasks, and chaining workflows together. OpenClaw taps directly into that excitement: it’s open, fast-moving, and built for people who want to experiment, extend, and orchestrate agents with minimal constraints.

At the same time, a different kind of question is showing up from business teams and Sentienta users: How does this compare to what we’re already doing in Sentienta? Not as a “which is better” culture-war, but as a practical evaluation: what’s the right platform for the kind of work we need to ship reliably?

The most interesting part is that both worlds are converging on the same core insight: a single, standalone LLM is rarely the best operating model for real work. The trend is clearly moving toward teams of interacting agents, specialists that can collaborate, review each other’s work, and stay aligned in a shared context. In other words, the wider market is starting to validate a pattern Sentienta has been demonstrating for business outcomes for over a year: multi-agent dialog as the unit of work.

In this post we’ll look at what OpenClaw is (and who it’s best for), then quickly re-ground what Sentienta is designed to do for business users. Finally, we’ll cover the operational tradeoffs, especially the security and governance realities that come with high-permission desktop agents and open extension ecosystems, so you can pick the approach that matches your needs for simplicity, security, and power.

What OpenClaw is (and who it’s for)

OpenClaw is best understood as an open ecosystem for building and running desktop agents – agents that live close to where work actually happens: your browser, your files, your terminal, and the everyday apps people use to get things done. Instead of being a single “one size fits all” assistant, OpenClaw is designed to be extended. Much of its momentum comes from a growing universe of third‑party skills/plugins that let agents take on new capabilities quickly, plus an emerging set of orchestration tools that make it easier to run multiple agents, track tasks, and coordinate workflows.

That design naturally attracts a specific audience. Today, the strongest pull is among developers and tinkerers who want full control over behavior, tooling, and integrations, and who are comfortable treating agent operations as an engineering surface area. It also resonates with security-savvy teams who want to experiment with high-powered agent workflows, but are willing to own the operational requirements that come with it: environment isolation, permission discipline, plugin vetting, and ongoing maintenance as the ecosystem evolves.

And that’s also why it’s exciting. OpenClaw is moving fast, and open ecosystems tend to compound: new skills appear, patterns get shared, and capabilities jump forward in days instead of quarters. Combine that pace with local-machine reach (the ability to work directly with desktop context) and you get a platform that feels unusually powerful for prototyping—especially for people who care more about flexibility and speed than a fully managed, “default-safe” operating model.

It is worth noting the recent coverage that suggests OpenClaw’s rapid rise is being matched by very real security scrutiny: Bloomberg notes its security is work in progress, Business Insider has described hackers accessing private data in under 3 minutes, and noted researcher Gary Marcus has called it a “disaster waiting to happen“.

A big part of the risk profile is architectural: desktop agents can be granted broad access to a user’s environment, so when something goes wrong (a vulnerable component, a malicious plugin/skill, or a successful hijack), the potential blast radius can be much larger than a typical “chat-only” assistant. Not all implementations have this risk, but misconfiguration can lead to an instance being exposed to the internet without proper authentication—effectively giving an attacker a path to the same high‑privilege access the agent has (files, sessions, and tools), turning a useful assistant into a fast route to data leakage or account compromise.

How Does OpenClaw Compare to Sentienta?

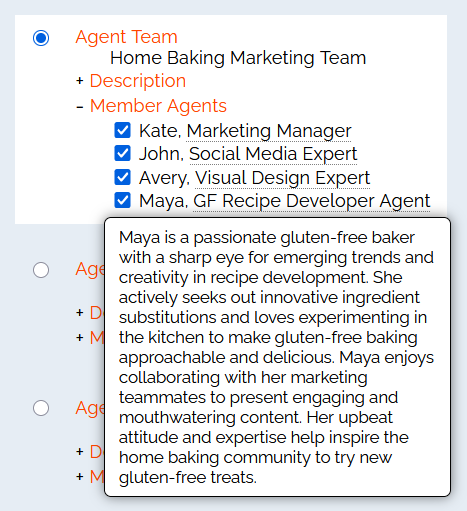

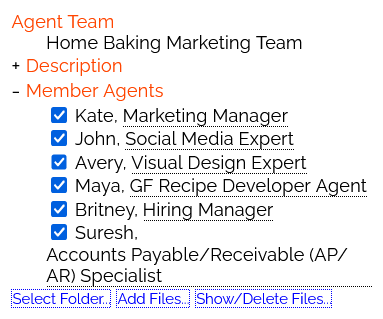

Sentienta is a cloud-based multi-agent platform built for business workflows, where the “unit of work” isn’t a single assistant in a single thread, but a team of agents collaborating in a shared dialog. In practice, that means you can assign clear roles (research, analysis, writing, checking, ops), keep everyone grounded in the same context, and run repeatable workflows without turning day-to-day operations into an engineering project.

It’s worth emphasizing that OpenClaw and Sentienta are aligned on a key idea: multi-agent collaboration is where real leverage shows up. Both approaches lean into specialization: having distinct agents act as a researcher, analyst, reviewer, or operator, because it’s a practical way to improve quality, catch mistakes earlier, and produce outputs that hold up better under real business constraints.

Where they differ is less about “who has the better idea” and more about how that idea is operationalized:

Where agents run: OpenClaw commonly runs agents on the desktop, close to local apps and local context. Sentienta agents run in the cloud, which changes the default boundary: when local data is involved, it’s typically handled through explicit user upload (rather than agents broadly operating across a machine by default).

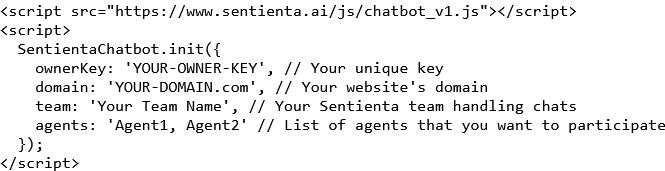

Time-to-value: OpenClaw is naturally attractive to builders who want maximum flexibility and are comfortable iterating on tooling. Sentienta is designed to get business teams to a working baseline quickly: Quick Start is meant to spin up a functional team of agents in seconds, with minimal developer setup for typical use.

Collaboration model: Sentienta’s multi-agent orchestration is native to the platform: agents collaborate as a team in the same dialog with roles and review loops designed in from the start. OpenClaw can orchestrate multiple agents as well, but its ecosystem often relies on add-ons and surrounding layers for how agents “meet,” coordinate, and share context at scale.

Net: OpenClaw highlights what’s possible when desktop agents and open ecosystems move fast; Sentienta focuses on making multi-agent work repeatable, approachable, and business-ready, without losing the benefits that made multi-agent collaboration compelling in the first place.

Conclusion

The bigger takeaway here is that we’re leaving the era of “one prompt, one model, one answer” and entering a world where teams of agents do the work: specialists that can research, execute, review, and refine together. OpenClaw is an exciting proof point for that future—especially for developers who want maximum flexibility and don’t mind owning the operational details that come with desktop-level capability.

For business teams, the decision is less about ideology and more about fit. If you need rapid experimentation, deep local-machine reach, and you have the security maturity to sandbox, vet plugins, and continuously monitor an open ecosystem, OpenClaw can be a powerful choice. If you need multi-agent collaboration that’s designed to be repeatable, approachable, and governed by default—with agents running in the cloud and local data crossing the boundary only when a user explicitly provides it—Sentienta is built for that operating model.

Either way, the direction is clear: AI is moving from standalone assistants to operational systems of collaborating agents. The right platform is the one that matches your needs for simplicity, security, and power—not just in a demo, but in the way your team will run it every day.

Introduction

Introduction